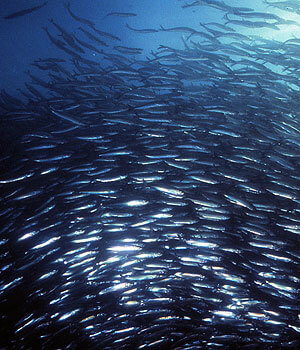

Here is a fishy tale of two species at the opposite end of the biological spectrum: a giant on the rise, and a tiny sliver of silver quickly becoming extinguished. The humpback whale’s recovery from near extinction is a heartening success story. Many whale biologists believe their population is now at 10% of historical levels, having bounced back from a mere 1% at their nadir less than fifty years ago. We hope their population is now large enough to survive a sudden shock such as another major oil spill in their habitat. Here’s a photo from our Alaska kayaking tour area of humpback whales lunge feeding on herring inside a bubble net.

Herring formerly thrived in stupendously large schools throughout the Pacific Northwest – from Washington through Alaska. But human impacts, some that we’ve discussed before in the Sea Quest Kayaking blog, began a crushing decline in their southern range about 30 years ago, recently reducing them to 5% of historical levels in much of Washington. This insidious decline seems unstoppable and has swept northwards into Alaska where estimates of 50% drops in the past 20 years are alarming biologists, conservationists, and fishermen.

As herring are the keystone species in this marine ecosystem, their departure will be devastating and we are already feeling the impacts. In the San Juan Islands and elsewhere in Washington, marine birds dependent on herring have experienced declines from 90-99%. In Alaska, the northern population of Steller’s sea lion has plummeted, forcing them on to the federal threatened species list. Countless other impacts are reverberating throughout the marine ecosystem as the herring biomass shrinks, including reduced food for salmon which in turn feed the orca whales, bears and eagles.

In the eastern half of Prince William Sound of Alaska, researchers have been closely following the fortunes of both humpback whales and herring. This was the site of the infamous Exxon Valdez oil spill of 1989 that lead to a total crash of herring in the sound. It was expected that some recovery would occur over the past 21 years, but this has not happened. In an amazing display of ignorance, some people are beginning to blame the recovering population of humpback whales for the inability of herring to bounce back! Somehow they are overlooking the fact that a century ago, before the hand of man was felt, both species flourished in the productive waters of Prince William Sound.

It is true that more humpbacks are eating more herring, and that some humpbacks are remaining in Alaska for the winter in recent years. But this is just a return to normality for the humpback whaless. Both whales and herring have evolved together over tens of thousands of years to balance out the predation. A more sensible analysis would look at the lasting effects of the oil spill. Recent news and published studies show that significant amounts of toxic oil remain trapped in beach gravel, possibly leaching out to reduce herring fertility. It’s no wonder that Prince William Sound fishermen still curse Exxon for the absence of herring. The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council, formed to oversee restoration of the injured ecosystem, and backed by a $900 million civil settlement with the petroleum company, says the reasons for the poor herring recovery remain largely unknown.

Note: Sea Quest offers kayaking tours in the far western portion of the 100 mile-wide immensity of Prince William Sound, far from the site of the 1989 oil spill. This part of the sound is still rich with feeding humpback whales, roving pods of killer whales, sea otters, nesting eagles, and abundant marine wildlife!